Confederate descendants and re-enactors will mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil War throughout the year. Events, such as today’s reenactment of the swearing in ceremony of Jefferson Davis, confederate civil way president, and a parade in Montgomery, Alabama, distorts history.

That the event occurred during Black History Month seems fitting. In observance of the sesquicentennial, below is the Richmond Times-Dispatch column I wrote in 2000 that sums up my arguments about why honoring the confederacy honors slavery. What do you think?

Now that we’re in the midst of the state’s Confederate History Month, I decided to take a closer look at what the Confederates were all about.

I started by reading the Confederate constitutions, specifically the Permanent Constitution adopted March 11, 1861. It is modeled after the U.S. Constitution but has some glaring differences.

Several deal with protecting slavery as an institution.

Those who argue that slavery wasn’t at the heart of the Confederates’ issues haven’t read this document, which was designed to protect and expand slavery.

It stipulated that no law “denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.”

As to the expansion of slavery in new areas, “In all such territory, the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress by the territorial government; and the inhabitants of the several Confederate States and Territories shall have the right to take to such territory any slaves lawfully held by them in any of the States or Territories.”

Alexander H. Stephens, who served as vice president of the Confederate States during the Civil War, made a speech in Savannah, Ga., shortly after adoption of this constitution.

As to the institution of Negro slavery: “This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and the present revolution,” he said.

On the newly established Confederate government: “Its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man. That slavery – subordination to the superior race – is his normal condition,” said Stephens, a slave owner.

Weeks later, Robert H. Smith, one of the framers of the document, told an audience,

“We have dissolved the late Union chiefly because of the negro quarrel.”

The last time I wrote about the reasons many African-Americans find the flying of the Confederate flag at statehouses or other public places reprehensible, I heard from many Confederate supporters who didn’t understand the gist of my argument.

So let me try again.

I understand that many of your ancestors didn’t own slaves. Or that they were fighting to defend their homeland, or fighting for states’ rights.

But I also believe none of them was fighting against the white supremacy that made black slavery an American institution for about 250 years.

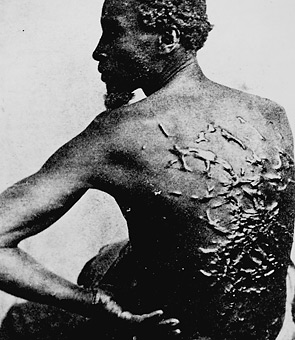

That the Confederates wanted to preserve their lifestyle – their culture – on the backs of the black men, women and children who made such a lifestyle possible cannot be argued.

And it infuriates the descendants of those slaves when the government decides to honor these Confederate leaders, this Confederate heritage.

Think about it. It’s an insult and, I would argue, a racist act for government to sanction Confederate symbols.

“In Germany, it’s illegal today to paint a swastika on a wall,” said Cheryl Johnson-Odim, head of the Liberal Education Department at Columbia College Chicago and an African-American historian.

“Some people may argue that it’s just a symbol of the Nazi party. But it’s an exact parallel to this case.”

Ron Walters, a professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, agreed.

“A lot of modern apologists for the Confederacy want to pull the slavery aspect of it apart from the rest of it and pretend there is some sort of pristine Southern [culture] apart from the institution of slavery, which undergirded it,” he said.

Walters has no problem with Southerners who want to honor their ancestors as long as they do it privately.

“The reason, of course, is that the Confederacy was defeated. It would be like proclaiming Nazi Week. It was a defeated power, a racist power, and it was oppressive to black and Native Americans and others. As such it is a regimen that should not have a place of honor in this society.”

Walters finds it “abominable” that Gov. Jim Gilmore issued the proclamation.

There is little use for “Confederate Heritage,” said Michael J. Birkner, chairman of the Department of History at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania.

“Huff and puff as much as they want, those [who] want to celebrate the Confederacy are celebrating a system that made chattel slavery its foundation,” Birkner said last week. “I know all the arguments about how most Confederate soldiers didn’t own slaves and many were focused mainly on states’ rights or, more likely, simply protecting their mates and their home turf. Perhaps people should simply celebrate the bravery of the common soldier.

“The Confederacy itself deserves to be dead and buried. It was a bad idea and a bad system.

“It is possible to separate reverence for ancestors who fought in the war or for the Southern fighting man from fond recollections of a pervasively racist and racially oppressive system.

“`Confederate Heritage’ fails to do that.”

Great article! I totally agree. I guess you will always have some Confederate ansestors who will never let this go…they refuse to recognize that THEY LOST!!!!!